Artist Grimanesa Amorós on the Value of Public Art

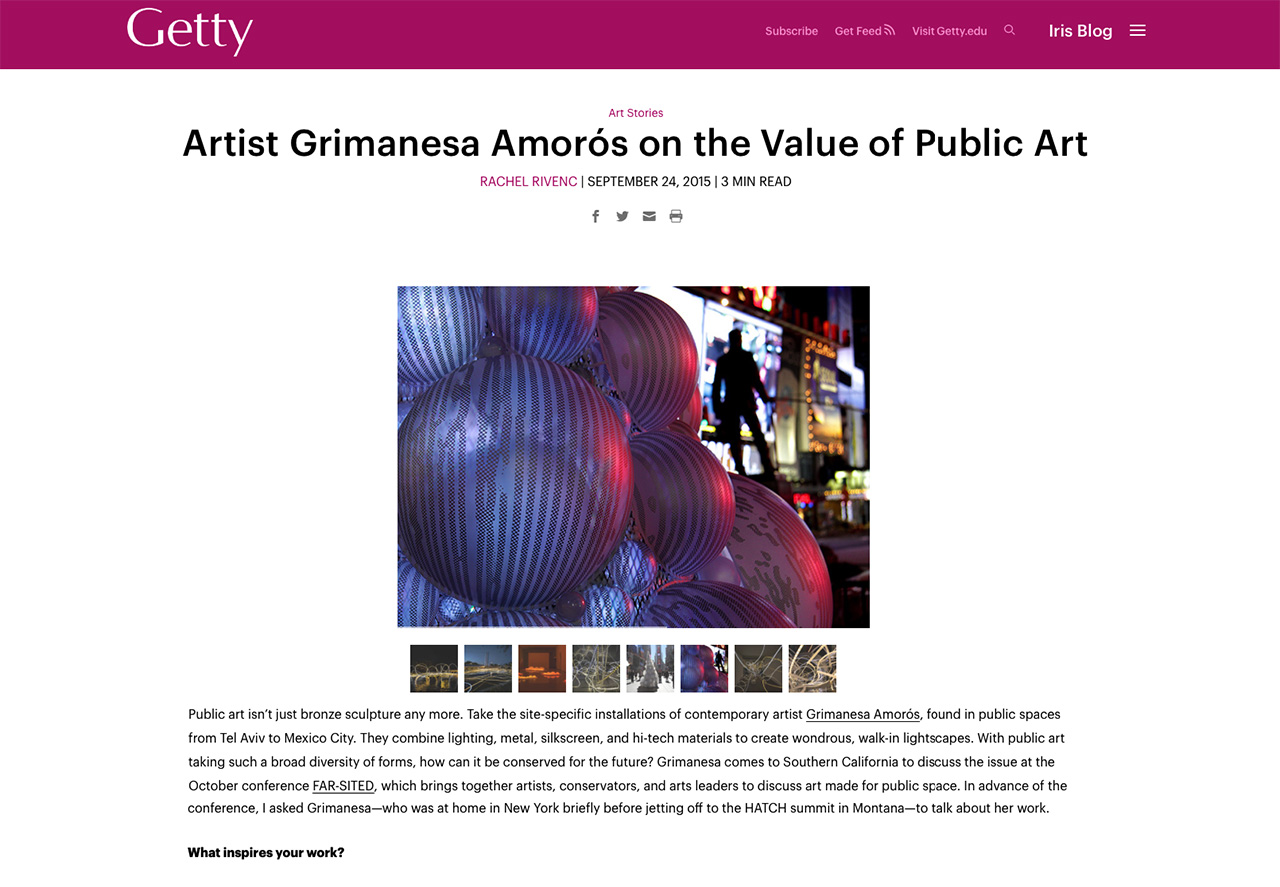

Public art isn’t just bronze sculpture any more. Take the site-specific installations of contemporary artist Grimanesa Amorós, found in public spaces from Tel Aviv to Mexico City. They combine lighting, metal, silkscreen, and hi-tech materials to create wondrous, walk-in lightscapes. With public art taking such a broad diversity of forms, how can it be conserved for the future? Grimanesa comes to Southern California to discuss the issue at the October conference FAR-SITED, which brings together artists, conservators, and arts leaders to discuss art made for public space. In advance of the conference, I asked Grimanesa—who was at home in New York briefly before jetting off to the HATCH summit in Montana—to talk about her work.

What inspires your work?

My current inspiration derives from nature and its natural elements, such as the Northern Lights and the Uros floating Islands in Lake Titicaca.

When I traveled to Iceland and saw the Northern Lights, it was a life-changing and deeply inspirational experience. At that moment I was fully immersed and amazed by the lights and the intensity of the colors. The lights are a core memory that I will store forever.

You’ve spoken about the influence of Peru in your artistic practice. What about it continues to inspire you?

I have many good memories of my native Peru. Since I was a child, living on the coast of Peru, I’ve always loved the beauty of the ocean; everything from the tides, to the colors, to the bubbles and the foam along the shore, specially around the month of March.

Off the coast of Puno, Peru, are the Uros Islands, floating islets made of totora reeds grown in Lake Titicaca. Everything, from houses to boats to watch towers, is made of these totora reeds. This truly fascinates me.

What made you want to pursue public art?

My experience in Iceland was a wow! I immediately thought how wonderful it would be to share this with others. Sharing one’s memories is sharing a piece of oneself. I’m intrigued by the accessibility and openness created by public art. I always enjoy seeing the expressions of viewers as they encounter my work.

How would you define public art? And what would you say is unique about the experience of public art, versus other art forms?

I would say what differentiates public art from other forms of art expression is that public art is site-specific and meant to be shared with others. The work has to generate a dialogue with its surroundings and community. A piece must be a part of the surrounding architecture or natural landscape.

I like to guide my viewers. My goal is to express an awareness of whatever the piece entails. I want them to think about the work and its surroundings.

Do you consider your work sculpture or installation?

My work is sculpture and installation at the same time. Like sculpture, it focuses on the subject and the interpretation of the viewer. Like installation, it is site-specific and creates a whole environment.

Your work incorporates complex custom lighting and high-tech elements, as well as materials such as aluminum, acrylic, and silkscreen. What are the challenges specific to creating this kind of art?

Each sculpture requires detailed planning: designing the structures the LEDs or domes are attached to (usually a truss system), drawing up a list of materials and equipment, and deciding how to pack and unpack the work. The budget is extremely important to the quality of materials used during production.

The entire process has a lot to do with the site where the work will be installed. Each site has its restrictions and constraints—currents, weather, buildings, sun, wind, building rules, time limits, use of materials, imagery. That’s okay, because as an artist, I use these constraints to help create a powerful piece.

How do you interest government leaders in supporting and conserving public art?

I am being invited to display more and more art in public spaces, so I believe that local and state governments increasingly understand the value of bringing art into their communities.

As for conservation, I don’t think much about it when I create my work! Indeed, the openness of public art makes conservation much more difficult. I do take the work’s surroundings into consideration, however. For example, my recent project GOLDEN WATERS has to be water-resistant and withstand Arizona temperatures of 110 to 117 degrees, so I did a lot of tests in my studio.

What are you looking forward to sharing with the audience at the FAR-SITED conference?

I’m looking forward to sharing some of the challenges I’ve encountered in installing, de-installing, and conserving both outdoor and indoor pieces.

Why do you think this an important time to be talking about the conservation of public art?

Art has the power to speak to people—particularly public art, because of its wider audience and its openness.

I’ve always been fascinated by viewers’ responses. Their wows, shares on social media, and comments make me feel I am on the right track. That also means my work has to be well cared for. Conservation is a challenge faced by artists as well. Discussing the conservation of public art is timely not only for me but also for everyone who thinks public art is important.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved. _______

Hear Grimanesa Amorós and Rachel Rivenc speak at FAR-SITED: Creating & Conserving Art in Public Spaces, a public conference taking place in Long Beach on October 16, 17, and 18, 2015. The event brings together artists, conservators, scientists, students, and arts leaders to discuss pressing issues of creating, displaying, and conserving art for public spaces. FAR-SITED is a collaboration between the University Art Museum at California State University, Long Beach, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Museum of Latin American Art. See the full schedule and register for one or more days here.

Read the article on Getty Blog: click here.

Download the article.