Between Presence and Absence:

New Works of Grimanesa Amorós

Marek Bartelik

Falling Tell Me Your Story essay by Marek Bartelik

One of Octavio Paz’s “Recapitulations” reads: “To open a poem looking for this and finding that-always something else.” I have been thinking about those words while looking at Grimanesa Amorós’s new series of works, Falling (2002) and Tell Me Your Story (2002-2003).

A few years ago, I wrote on Amorós’s Fotomana (1998-2000), an installation of rectangular panels made of cotton pulp mixed with various organic materials, which depict silhouetted, inchoate animals, people, and houses, with handprints on the backside of the panels. Created in response to the richness of cultures and artistic expressions of West-Africa-which the artist had visited on a NEA grant and an Art International traveling grant in 1994- those playful works marked a departure in her outlook on art. In Fotomana, Amorós’s art reached a new level of formal maturity be enhancing the technical proficiency, known from her earlier expressionistic paintings, with refined and sensuous treatment of surface. Perhaps more surprisingly, after returning from Africa she reconsidered her identity, and, as a result, reconnected with her Peruvian roots. She discovered an uncanny familiarity, particularly in Ghana. Not only do Peru and Ghana, once part of the same continent, have comparable climates and food sources, but they also share similar beliefs and artistic sensibilities. Mesmerized by the timeless beauty and the sensual richness of West Africa’s landscapes and peoples, in her art she chose not to address the immediate socio-political aspects of life in the region, perhaps embracing the ambiguity of visual communication growing from the discursive space of the Nineties. “[T]here are issues worth advancing in images,” argued Dave Hickey, “worth admiring; and the truth is never ‘plain,’ nor appearances ever ‘sincere.’” In the times of the emphasis on cultural pluralism, the personal was recognized as political. Amorós viewed her journeys to other places as an extension, and expansion, of her experience in New York perceived as a reflection of broader contemporary problems.

Art can provide a lasting testimony to deadly destruction when it witnesses a tragic event, but, then, it needs to rise above the singularity of one’s experience, exceeding its own limits. “Art has come back to me slowly,” writes Amorós in her statement for Falling. “It took me quite a while to deal with the destruction of the Twin Towers…To restore my sense of balance I reverted to what has always been my way of responding to life – my art.” The artist chose to engage in a fragile process of healing by speaking about her pain. “The drawings,” Amoros notes, “are my response to the scenes and moments I witnessed on September 11th: people waving white handkerchiefs from the windows of the towers, amorphous yet painfully recognizable shapes falling down, and the clouds of white dust.”

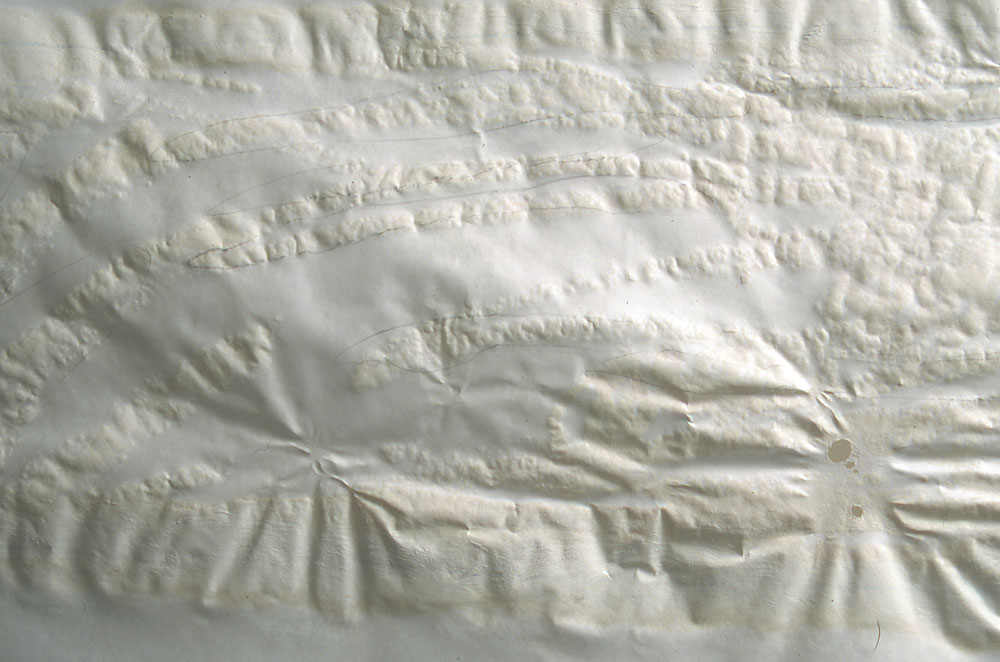

In spring 2002, Amorós took advantage of an opportunity to work within a residency program at the Santa Fe Art Institute in New Mexico, between October 2001 and May 2002 run for the artists from lower Manhattan, whose lives were affected by the terrorist attack on September 11th, 2001. Falling is a series of eleven large mixed media drawing (40 inches x 13 feet each) on Tyvek paper, intended for display as an installation and accompanied by a piece of music specially composed and “aimlessly” looped for continuous playback by Jim Wilson. Amorós chose Tyvek paper, commonly used as insulation material for walls, to emphasize the connection between her work and the inner structure of the buildings the lost presence of which she was to commemorate. The choice of the thick paper imbued with impenetrability could be also connected to the artist’s need to secure a sense of durability of her work.

The undulating drawings form vertical scrolls, descending the wall and folding flat on the floor. Some of the “folds” are kept in place on the floor by small casts of body parts – the artist’s own taken during her pregnancy a few years earlier. The images were executed with graphite and high-pigmented oil paints in stick and additionally affixed to the surface by a heat fun that melted the pigments and occasionally made small holes. The heat gun became, in fact, Amorós’s unconventional brush. The staged act of burning was an obvious reference to the tragedy of September 11th 2001, while the small holes could be viewed as marks of scarification, with paper serving as an analog of skin. The pictographic images in Falling recall those in Fotomana, but they are much more extemporaneous and evanescent, as if their destiny was to vanish. Their presence is almost “fluid,” making them look like anthropomorphized blood cells spilling outside of the invisible body into an intricate and undetermined space of vision. While the allusive drawings formally mimic the verticality of the Twin Towers, they take on a role of weightless beams of light that descend to our feet.

The memories of September 11th have remained frozen in time, between what was experienced then and what has been possible to visualize now. They form a translucent zone of remembrance in which the individual stories do not recreate the event, but they fight against being squeezed into official history by staying vulnerable, random and, perhaps, absurd. In my recollection of that early day of fall 2001, the victim’s faces are immobilized in photographs of the beloved posted on walls around New York City. They form a frieze of memory, communicating the frailty of human condition, at any time and anyplace. Nobody dared to remove those appeals to life from the walls, but they slowly deteriorated, washed out by rain. That was when for many New Yorkers the Twin Towers “fell down” for the second time. And those noisy sirens of fire engines sounded with an additional urgency, as if transmitting the succinct cry of souls. They were heard even if many had reasons to insist on the absence of the soul in the presence of raging fire, which for a moment grew to an apocalyptic dimension of burning down the world, also known as ekpyrosis. Then, two beams of light appeared, called Tribute to Light. They were “ghost limbs” conceived by a team of artists and architects as mnemonic devices, emanated from forty four enormous searchlights. They rose into the sky from a lot adjacent to the Twin Towers, finding their way through pollution and clouds, as if insisting on the power of illumination.

That day, I taught the history of Renaissance art to students at Cooper Union in downtown Manhattan. In a darkened viewing room, two images emitted from the slide projectors appeared side by side on a large screen, perpendicular to the beams of light that carried them through the space. The beams of light mimicked the falling Twin Towers, the images on the screens were “tributes to enlightenment.” We talked about differences between Raphael’s Alba Madonna (1510) and Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (c.1535), contrasting a mathematical precision in one to a bizarre over-refinement in the other. Being in the paintings, we seemed to witness the baby comfortably sitting on his mother’s lap in Raphael’s work gradually sliding off into indetermination in Parmigianino’s work. Via the path opened by Roland Barthes, we looked for a third meaning in reading images, without succumbing to the posturing of the academic discourse. That third meaning, called obtuse, is a supplementary one to more obvious ones of communication and signification, the one which our “intellection cannot succeed in absorbing, at the epitome of a counter-narrative…counter-logical and yet ‘true’.” Counter-logical and yet “true” was our experience that day. Like the film still in Barthe’s field of vision “offers us the inside of the fragment,” Amorós’s art endows individual experience, both physical and mental, with significance by downplaying the importance of narrative trope for the sake of montage and verisimilitude.

The presence of death usually enhances our sense of life, with detours. Amorós’s installation Tell Me Your Story was conceived in fall 2002 during her residency at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, a working retreat for writers, visual writers, and composers, located at Mt. San Angelo, a large estate in Amherst County, Virginia. In searching for contact with the local community, Amorós interviewed twenty nine people from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (kitchen, office, and maintenance staff) and from Sweet Briar College (library staff, students, and professors). Each person was asked two questions: (1) were you born in the vicinity of Lynchburg, or did you move here from somewhere else? And (2) what are your reasons for living/staying in the region? The answers were straightforward. People chose the area because that was where they had strong family roots, or they liked the local landscape and the weather. Amorós approached the challenge to interpret those “predictable” answers with the help of basic mathematics. After learning that three options exist for calculating statistical average (the mode, i.e a statistic that appears most frequently; the median, i.e. a middle number in a list of statistics; and an arithmetic mean, i.e. a simple type of average), she converted her private polling into visual patterns, in which individual experiences were grafted on working the best in different cicumstances. The images are supposed “to be ambiguous symbols,” she explains, “to represent the references people made to landscape, climate, and family.”

Tell Me Your Story consists of three long horizontal drawings (2.5 feet by 14 feet each) placed parallel to each other and three additional ones of the same length following each other in a row. The work is executed on Tyvek paper in a similar technique to Falling, with a difference of using titanium zinc white and zinc white as sole colors. The monochromatic color scheme has been chosen to “merge” the work into the wall. Ichnographically, the artist has reverted to the images of body parts, considering it as essential for the non-verbal, performative, and telekinetic communications. At the same time, in Amorós’s visualization of her conversations with the inhabitants of the Lynchburg region, body parts approximate real people, and she occasionally inscribes them with the names of the interviewed persons. Amorós emphasized the rhythmic, modular, and stream-of-consciousness aspect of her graphic interpretation of the answers. To enhance sensory expressiveness and the panoramic quality of her work, Tell Me Your Story is dramatically lit and accompanied by a musical composition, a result of Amorós’s collaboration with the composer Laura Koplewitz, a kindred spirit she met during the residency in Virginia. “Our concepts in the creation of the soundtrack,” Koplewitz notes, “included a desire to draw the listener into a palpable feeling for a local environment (bird sounds, cows mooing; the close-up clackety-clack of a train slowly making its way across the countryside) along with larger gestures in the orchestral palette (strings, horns, woodwinds), that provide a sense of an ‘open vista’ and visual sense of a camera that pans from a very distant place across the horizon.

Nearly two years have passed from that day when the Twin Towers fell down, still the frieze-like Tell Me Your Story brings back the memory of the photographs along New York street following September 11th, taking me where I did note expect to go: looking for this and finding that. What continues to fascinate me in Amorós’s work is its unpredictability and expandability. She searches to express complex emotions by both relying and questioning her subjectivity. She seeks to stretch the boundaries of her pictorial field. Her working process is totally physical, yet her art increasingly contemplative, echoing the words: And what happens with regard to such walls and variegated stones is just as with the sounds of bells, in whose jungle you may find any name or word you choose to imagine.